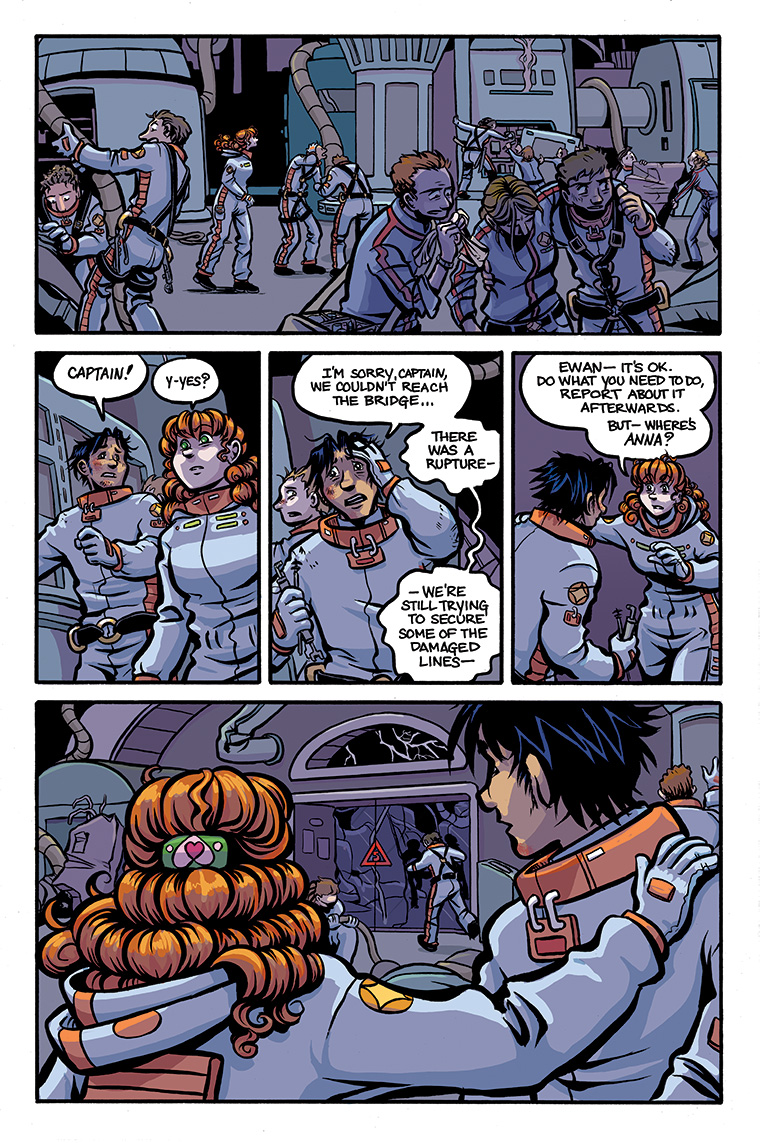

Is Fusella any closer to getting her head together as she faces this disaster? Well, um. I very much appreciated and enjoyed all the debate last week, and the only thing I will add is that this scene may possibly read differently as a whole chapter, rather than the week-to-week. We’ll have to wait to find out, I guess!

Galaxion

Life. Love. Hyperspace.

I guess this is kind of like Kirk discovering that Spock went to the engine room… D:

Nevertheless, I hope Anna’s okay.

Also: in the arched window, is that lightning, or something else?

@Insectoid. It could be cracked or broken glass.

Good point, David… although, if the glass were cracked or broken, wouldn’t that make the airlock no longer secure?

Depends on how many layers of glass there are. IIRC, Apollo and Shuttle spacecraft had 3 layers of glass in their windows as redundancy; one breaks the other two can still keep the seal. I’m thinking the Deep Freeze has a similar safety feature.

Tara, this is kind of repeating last weeks comment, but you can be happy that there’s so much discussion about your characters’ abilities, rather than, say, about their hair or body shape. And speaking of the visual part of your storytelling, I think that you really get accross the physical chaos, the psychological shock, and the dogged determination to clear it up.

My experience in the computing industry is that in a crisis the best thing a manager can do is get out of the way and let the team get on with fixing the problem. If a manager tries to intervene, they’ll only slow down a good team dealing with a temporary short term panic. The manager should be involved later when you report what the issue was, how you fixed it, what longer term work and resources are needed to fix it properly (in the likely case you had to do a quick nasty fix). And most importantly of all, what needs to be done to reduce the chances of something like it happening again.

The only time it is worth a manager wading in during a crisis is if their team is of poor quality or not working well together. Often the best thing to do even then is to tell the poor quality staff to go away and do something else, because they’re slowing the good staff down with their questions. If you actually need to micromanage the crisis then you’re probably doomed to failure anyway.

I realise the military model is to micromanage everything all the time (and that’s one of the reasons I’ve never gone anywhere near a military career). I’m not going to pass judgement on whether the military way is better or worse, but I will note that Galaxion is a civilian ship used to doing things the civilian way.

I might add that a manager may need to get her/his hands dirty in a crisis if the needed hands are no longer available for one reason or another and the manager is able to fill in. Not ideal, but sometimes better than the alternative.

Not a military man myself, but I note that a mark of good commanders is to be able to know when they can trust subordinates with orders, and when they need to step in. Generals cannot order every soldier around or choose every objective. They trust their subordinates to handle more detailed orders, and their subordinates trust THEIR subordinates with even more details and so on. A general or colonel micromanaging something should only happen if the entire command chain between general and enlisted has been wiped out.

This particular situation is less a military model and more a civillian emergency response one, which is more my area of expertise. Many of the same practices and terminologies as the military are used in emergency response; strategy, tactics, logistics, chain of command, unity of command, etc. The essential point is that you have one person in charge who is not part of the operational response (i.e. someone who is not cutting metal, fighting fire, searching for victims, or providing care) who can keep the big picture and give effective strategic orders to subordinates to carry out, and that those subordinates are themselves separated into teams with command structures and specific duties.

How this might play out aboard Galaxion: Fusella assumes command (Scanvia has committed to rescue operations and has “passed command”) and starts gathering data. She tasks several crewmembers who are not injured with establishing communications to the bridge and removes herself from the immediate scene. Ideally, she returns to the bridge as soon as communications have been reestablished; hopefully there is a backup system that can be used quickly and efficiently. Once away from the immediate scene, she begins communicating with the rest of the ship, requesting information on potential hazardous materials or fumes that have been spilled, hull integrity, numbers of injured, numbers of trapped requiring rescue, and numbers of fatalities. She assigns several crewmembers to each individual task, with the implicit understanding that they will preform their assigned task without questioning it. Because of the number of voices now clamoring for her attention, she cuts down on her workload by assigning one crewmember to be the operations chief and assigns another crewmember to take over logistics, finding and procuring necessary tools, materials, and non-essential personnel to help out with the emergency, and also figuring out the ship’s location in relation to other resources. Two more crewmembers are assigned to planning on a ship-wide scale. Now Fusella is only talking to three or four other people, who are in turn only talking to five to six, and so on down the line. As needed, more people can be assigned to various problems as they arise; what to do with the deceased bodies, how to deal with supply shortages, how to get the engines back online, etc.

Obviously, while it is standard practice in my world, it doesn’t make for great stories or drama, and so is not a common literary device. Safety culture is, unfortunately, boring; people want to get their hands dirty in operations, not sit and look at maps and diagrams. So you frequently have operational situations where there is no safety culture, no drills, no consideration of the potential for disaster, and way too much hubris and “it won’t happen to us.” What that means is, when the manure hits the rotary impeller, you get chaos, nobody in charge, operational blind spots, and further injury and damage. At the moment, the Galaxion is in this situation; the ship is damaged, there are casualties, nobody knows what’s going on and NOBODY IS IN CHARGE.

Staring into space for five minutes is the way of doing things?